The Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) Program is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) primary grant program for addressing flood risk to vulnerable National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) properties. The recently signed Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) (IIJA) appropriated $3.5 billion to the National Flood Insurance Fund for the FMA program. This breaks down to $700 million over the next five years, starting with fiscal year 2022. This is a significant investment on FEMA’s behalf to provide funding to reduce the number of properties currently at risk of flooding and reduce the number and value of future claims to the NFIP.

In addition to the funding, FEMA is challenged to consider if the dollars are truly reaching the most vulnerable communities and how the additional funding will ultimately reduce their risk. The highest priorities for FEMA should be streamlining and improving the program, continuing to add benefit for disadvantaged communities, as well as an enhanced focus on climate adaptive projects. If these priorities are addressed, FEMA may see a more equitable FMA program that flourishes in benefit of disadvantaged, flood-prone communities nationwide.

History of FMA funding

As a result of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012, the primary source of funding for FMA has been NFIP premiums. As such, the primary goal of the FMA program has been to award projects with the greatest potential to maximize savings to the NFIP principally through mitigation projects that protect or remove Severe Repetitive Loss (SRL) and Repetitive Loss (RL) properties from flood hazards. FEMA uses the SRL list as its primary source of eligibility information, despite this list being fraught with inconsistencies and outdated information.

Repetitive Loss (RL): A property that has incurred flood related damage on two occasions, in which the cost of the repair, on the average, equaled or exceeded 25 percent of the market value of the structure at the time of each such flood event.

Severe Repetitive Loss (SRL): A property that has had four or more separate NFIP claims payments have been made with the amount of each claim exceeding $5,000 (including building and contents), and with the cumulative amount of claims payments exceeding $20,000; or two or more separate claim payments (building payments only) where the total of the payments exceeds the current value of the property.

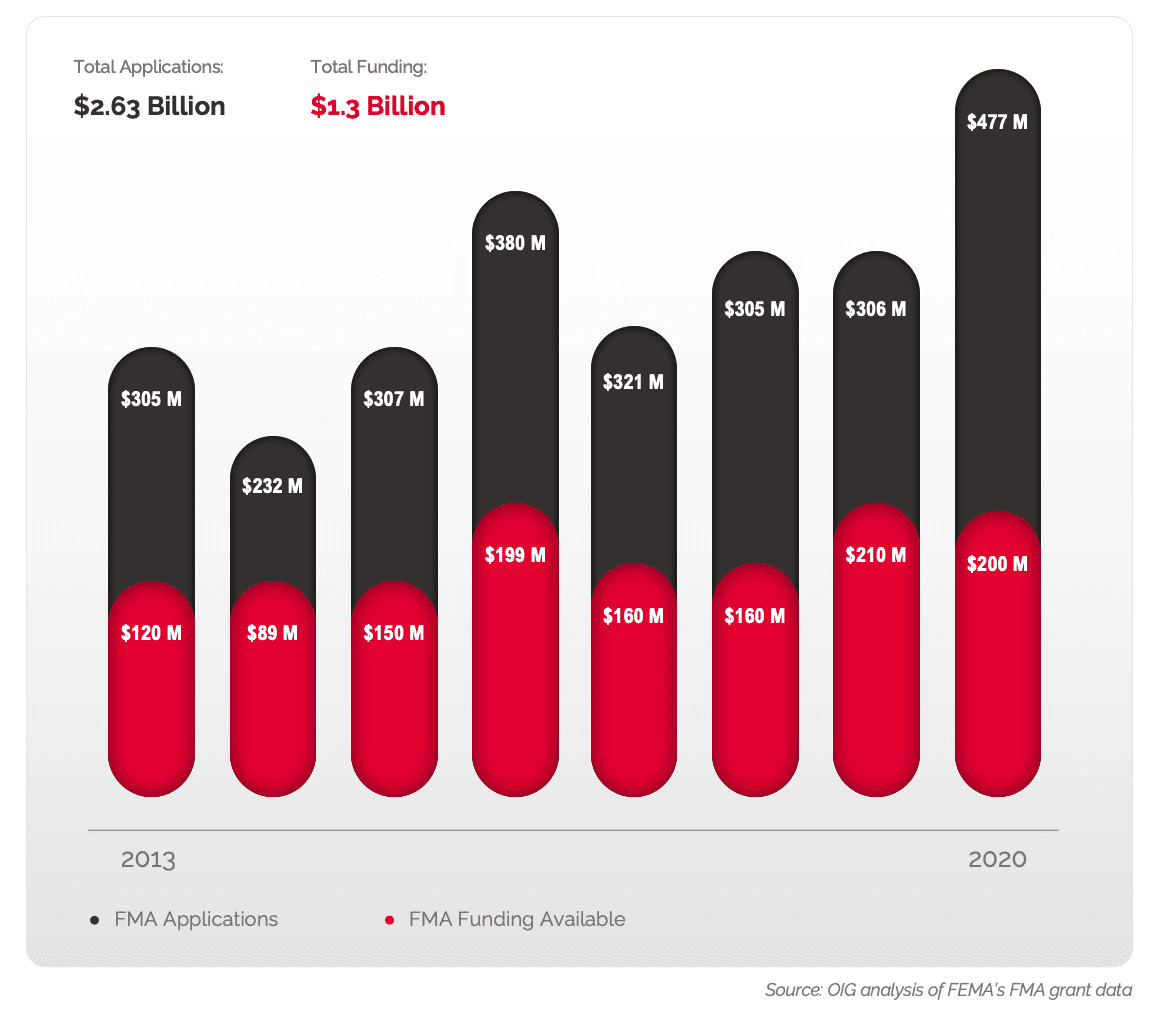

As reported by the Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General (OIG) in 2020, $1.09 billion was allocated in FMA grants from 2013 to 2019. Since 2013, demand for this funding source has exceeded available funds (Figure 1). In 2020, FMA received $477 million in applications, more than double the amount allocated, which demonstrates an increased need for mitigation dollars that were, until this point, not made available for flood ravaged communities. Additionally, the report found that, on average, FMA projects took 2.7 years to complete from the date of application submission. For a household whose home is no longer habitable, 2.7 years is unacceptable.

Figure 1 FMA Applications compared to Available Funding (2013-2020)

This figure was adapted from a DHS OIG Report (OIG-20-68, 2020), p. 5

Types of projects historically funded by FMA

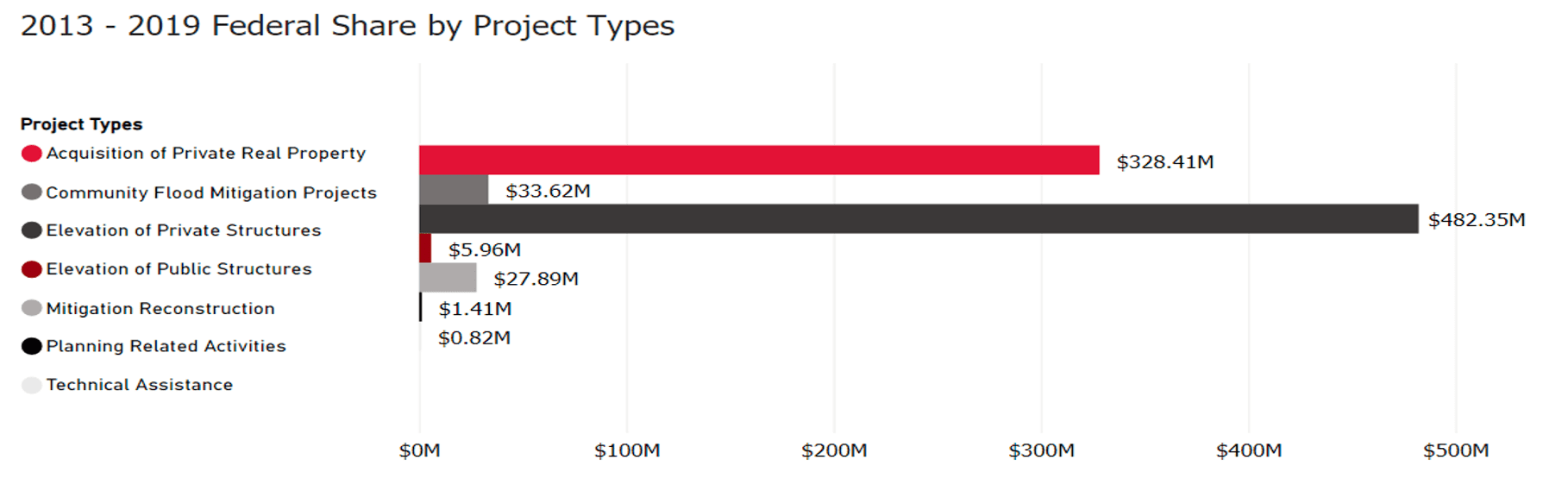

The primary objective of the FMA program is to reduce or eliminate flood risk to SRL and RL properties by providing mitigation funding opportunities to address these vulnerabilities. To further incentivize the mitigation of these properties, the FMA program covers 100 percent of costs for the mitigation of SRL properties and 90 percent of costs for the mitigation of RL properties. Individual flood mitigation measures—largely property acquisitions and structure elevations are the majority of the projects funded under FMA. Between 2013 and 2019, the FMA program invested $328 million in the acquisition of real property and $428 million in the elevation of private structures. Other project types received substantially less funding (Figure 2).

Figure 2 FMA Federal Share by Project Type (2013-2019)

Where are FMA funds allocated?

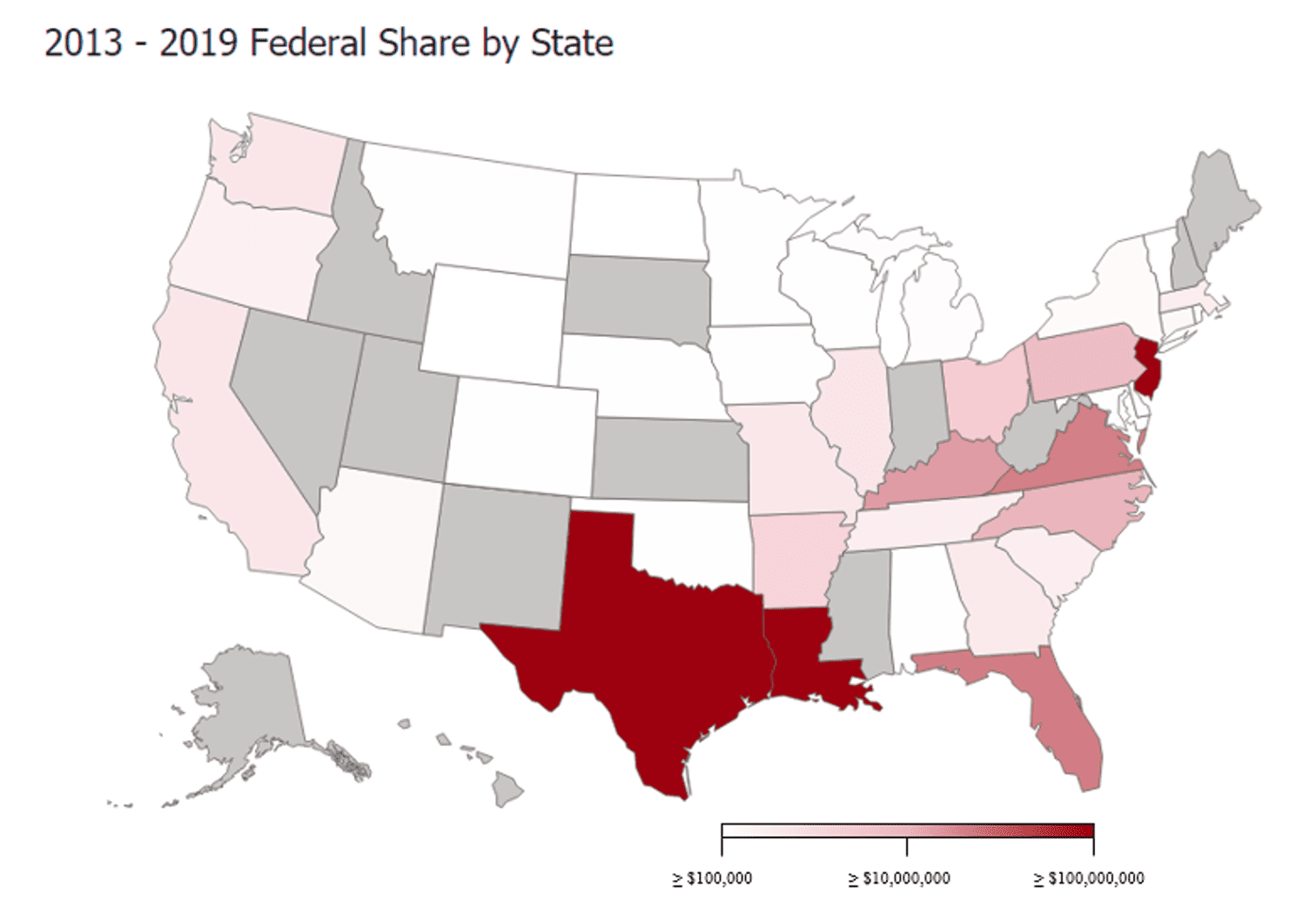

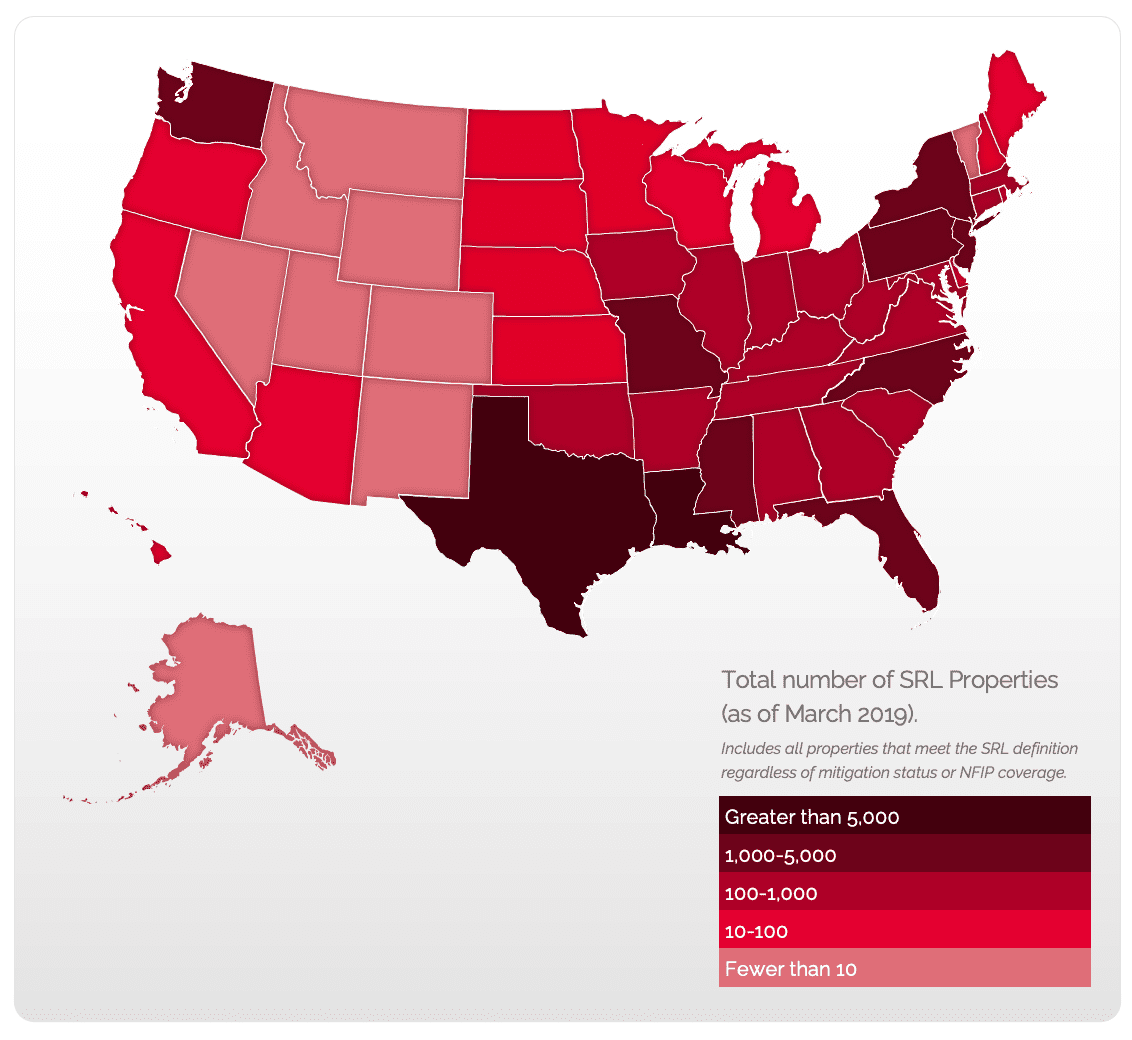

States with the highest number of NFIP properties, and especially SRL and RL properties, receive the most FMA funding historically. From 2013 to 2019, Texas, Louisiana, and New Jersey received the most FMA funding (Figure 3), which is consistent with the location of SRL properties. One of the outliers is Mississippi, which has a high number of SRL properties, but reports no FMA funding in those years. Which brings us to a challenge of the FMA program – why are some communities, with demonstrable need, underrepresented in the distribution of FMA grants?

Figure 3 FMA Federal Share Awarded by State (2013-2019)

Figure 4 Total Number of SRL Properties by State (as of March 2019)

FMA Program Obstacles

Application Submission and Project Cost Effectiveness

To begin with, the complexity of the grant application process and significant resources needed at the local government level to develop those applications discourage many communities from applying. These challenges contribute to either state or local decisions not to pursue FMA and their ability to be successful in obtaining funding.

FEMA’s FMA program, as with the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) and Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) grants, requires a very thorough and complex application to be submitted for the national competition, most of which is hard for communities to navigate on their own.

The FMA application also involves a Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) to evaluate if the risk reduction benefits of the project outweigh the costs to implement the project (e.g.,, buyout, elevate or otherwise mitigate the at-risk buildings). FEMA has taken steps to streamline cost-effectiveness by making revisions to the value of pre-calculated benefits. Pre-calculated benefits simplify the BCA for many individual flood mitigation projects by providing a standard value for benefits rather than requiring the community to conduct a full BCA.

Paperwork Overload

Another challenge to participation in the program is the burden to individual property owners. For example, the documentation burden can be significant since some of the households may not have NFIP documentation readily available. Further, property owners can be subject to prohibitive upfront or out-of-pocket costs—especially for elevation projects. This is acutely true in communities with socioeconomic disadvantages and in areas that have experienced repeated flood events. Elevation projects will often require the property owner to obtain property surveys, design plans, elevation certificates, and other technical information that must be submitted during the application process. In addition to documentation collection, as noted by the 2020 OIG report, property owners are often subject to a long waiting period before their home is purchased or mitigated.

Ultimately, property owners depend on the willingness and ability of state and local officials to participate in the FMA program. Without assistance to local jurisdictions to prepare project applications, mitigation of these at-risk properties and communities will continue to be slow and inequitable.

Closing the gap: Getting funding to communities in need

With the bump in funding that FMA is receiving through the IIJA, will necessary funding reach those communities that have been left out or underrepresented in the program? Mitigation across flood prone American communities is only going to become more urgent as the impacts of climate change worsen. These impacts will impact disadvantaged communities in disproportionate ways so the more we invest today, the better. Mitigation saves $6 on average for every $1 spent on federal mitigation grants.

With the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Initiative (Executive Order 14008), the FMA FY2021 program intends to prioritize projects that benefit disadvantaged communities. The FMA Notice of Funding Opportunity for FY21 grants includes additional scoring points for Project Scoping and Community Flood Mitigation Projects that benefit disadvantaged communities (as measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index).

In addition to the changes from the Justice40 Initiative, the IJIA expanded the federal cost share to 90 percent for a property that 1) is located in a census tract with a CDC SVI score of not less than 0.5001 or 2) serves as a primary residence for individuals with a household income of not more than 100 percent of the applicable median income.

To utilize this new funding in the most equitable way, several key areas can be improved to further the goals of the FMA program.

- FEMA can provide communities accurate NFIP and SRL data more readily.

- FEMA can incentivize homeowner participation by streamlining the application review and award process.

- States can improve their subapplicant outreach to reduce ineligible or non-competitive projects and improve the viability of FMA subapplications submitted.

- FEMA, state, and local governments can make equitable choices in prioritizing projects (e.g., prioritizing primary residences over secondary or income properties).

What’s next?

Interested states and communities should prepare for this upcoming funding by beginning outreach to communities to understand need and level of interest in participation and to provide technical assistance if needed. Additionally, states that have received FMA funding in the previous year can apply for FMA’s Technical Assistance program which provides funding to states to maintain a viable FMA program over time

As with the BRIC program and HMGP, FMA offers funding for Project Scoping activities. The funding caps are $300,000 for individual flood mitigation projects (e.g., acquisitions, elevations, mitigation reconstruction) and $900,000 for community flood mitigation projects. For individual flood mitigation projects, a community could apply for Project Scoping to conduct homeowner outreach, identify priority project areas, develop a Benefit-Cost Analysis, assist homeowners with documentation collection, and develop a complete FMA application. A similar strategy applies to project scoping for community flood mitigation projects.

Conclusion

As our climate continues to change, the importance of this funding cannot be overstated; and by ensuring all communities in need receive this funding, we are collectively buying down our risk to future disaster impacts. Furthermore, reducing or eliminating current barriers to entry into the program will help ensure funding reaches those who need it most, when they need it.

Vanessa Castillo is a mitigation and planning consultant with experience in the implementation of the FEMA mitigation programs. Before joining Hagerty, she was a Mitigation Specialist with the state of Colorado where she contributed her expertise to the successful implementation of more than $65 million in Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) for Colorado’s largest disaster.

Lauren Dozier is a Senior Managing Associate and a subject matter expert (SME) in disaster recovery. Lauren has spent the past 11 years in preparedness, mitigation, and FEMA Public Assistance (PA). Her knowledge and experience of financial recovery has assisted communities nationwide to recover from and prevent future disasters.

Amelia Muccio is the Director of Mitigation at Hagerty Consulting and a SME in disaster recovery. With over 15 years of experience in public health, disaster preparedness, mitigation, and financial recovery, Amelia has helped clients obtain $5 billion in federal funds after major disasters, including Hurricane Sandy, the California Wildfires, and Hurricane Harvey.

Want to know more about FEMA mitigation programs?

Please fill out the form below and one of our mitigation experts will be in touch!

hbspt.forms.create({

region: “na1”,

portalId: “9315766”,

formId: “5371b4fd-b17d-403a-afb4-72b200380955”

});